Author: Burt Rutherford – Working Ranch Magazine

There’s another fight brewing near Columbus, the small southern New Mexico village that was the site of the first military incursion into the United States. In March 1916, Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa led an army of about 1,500 guerillas across the border to stage a raid against the small American town of Columbus, New Mexico. Villa and his men killed 19 people and left the town in flames, according to History.com.

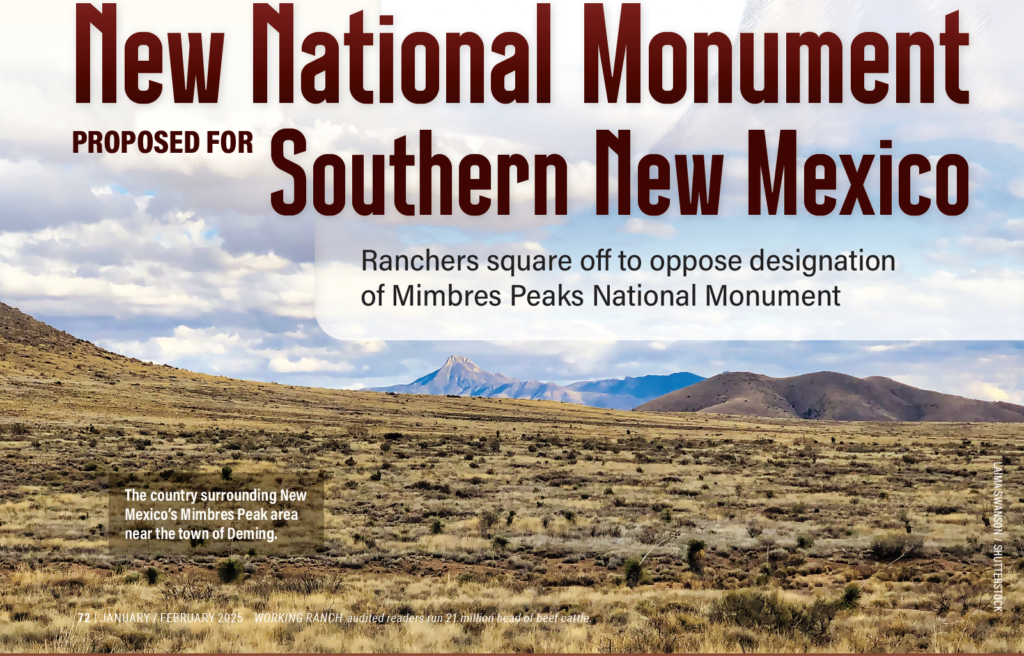

In contrast, the present-day fight over establishing the Mimbres Peaks National Monument is a war of words and agendas. It’s centered just up the road in Deming, New Mexico, and even farther east in Las Cruces.

On one side are the ranchers and others who oppose establishing yet another national monument along the U.S.-Mexico border. On the other side is a coalition of environmental groups that favor protecting the natural and cultural resources encompassed within the proposed borders.

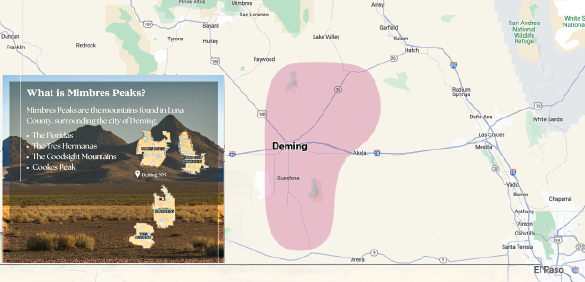

And the proposed area is significant — somewhere around 245,000 acres, roughly 383 square miles.

BACKGROUND

The land within the proposed monument boundaries is a patchwork of federal land under the purview of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), state-owned property, and ranches that operate both on deeded land and grazing allotments leased from the state and BLM. There are four mountain ranges within the proposed boundary.

New Mexico is home to a handful of National Parks and National Monuments. The two closest to the proposed Mimbres Peaks National Monument are the Organ Mountains- Desert Peak National Monument near Las Cruces and the Gila Cliff Dwellings near Silver City. The effort to put the wheels in motion to declare a new national monument began with a news conference in December 2023.

WHAT THE PROPONENTS SAY

The coalition behind the effort to create the Mimbres Peaks National Monument is called Protect Mimbres Peaks. Organizations involved in the coalition, according to its website, are the Sierra Club, NM Café, Friends of the Floridas, The Semilla Project, New Mexico Wildlife Federation, Outdoor New Mexico, Friends of the Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks, Las Cruces Green Chamber of Commerce, and New Mexico Wild. Listed as supporters are the Conservation Lands Foundation, The Wilderness Society, and the Native Lands Institute.

“For the coalition as a whole, there are various cultural resources, a lot of biodiversity, as well as there’s a lot of historic war items that we would like to see preserved for future generations, as well as many benefits that come with those protections, such as having more field staff with the BLM, such as having a local ranger, outdoor recreation planner, biologist and manager,” said Antoinette Reyes, Southern New Mexico and El Paso organizer for the Rio Grande Chapter of the Sierra Club.

There are different types of monuments, managed by various federal agencies. “This one, because it’s already BLM land, stays as BLM, where BLM prioritizes diverse and multiple uses. So, having some of these staff people is important, and also the type of land designation puts the land in a higher place when it comes to federal funding,” Reyes said.

Then there’s the land itself. “As a state, we have the second most native mammal species, we have the fourth most plant diversity in the country, as well as having along the border area, a lot of migratory paths, especially for birds and some small to medium and a few large mammals as well,” she said, speaking on behalf of the Rio Grande Chapter of the Sierra Club rather than the Protect Mimbres Peaks coalition. “And so, since there are already two other monuments not too far away, this would essentially be one of the first monument corridors in the country, which would bring even more tourism.”

Increased tourism is among the benefits touted as a reason to designate the new monument. Citing the Organ Mountain-Desert Peaks, which has been a national monument for around 10 years, Reyes said there has been a 300% increase in visitation, using counters at the visitor center and cell phone data to record visits. According to an economic study conducted by BBC Research and Consulting and released by the Las Cruces Green Chamber of Commerce, “New non-local visitors to the national monument would directly spend about $10.2 million per year under the medium visitation scenario ($7.3 and $13.1 million, respectively, under the low and high visitation scenarios) per year on goods and services, creating 88 new jobs under the medium visitation scenario (64 to 113 new jobs, respectively, under the low and high visitation scenarios) in tourism and recreation- facing sectors like accommodations, food service, and retail sales.”

When it comes to ranching, Reyes points to the Organ Mountain-Desert Peaks. “So, as an example, for the Organ Mountains in terms of ranching, it stayed the same for how many acres and land they have for it. I know that the number of permittees that have applied has increased since it became a monument. But even with or without the increase, the number of available land has stayed the same in all of their alternatives,” she said.

The alternatives come from BLM’s recently released management plan for the Organ Mountain-Desert Peaks. “The only other area that’s multi-use that’s negatively impacted is mining.” That applies to new mining claims. Existing claims would be grandfathered in, she said. “But aside from that, all other uses stay the same.”

On private land that would fall within the proposed boundary, she said ranchers could make improvements on their own property and roads. “But sometimes there is more red tape to expand a road, or to make more lanes, and stuff like that.”

Reyes said she understands ranchers’ concerns and there have been a lot of good questions. “I know that since it’s so early in the process, they haven’t been able to get all the answers they would like, but there’s been a continuing dialog. I would just stress… the boundaries aren’t completely fixed. It’s still so early in the process that people have even considered changing the boundaries to preserve mining since rockhounding is such an important thing in the community.”

According to Reyes, the timeline for establishing the Mimbres Peaks National Monument isn’t clear. “Most national monuments that have been proposed have, on average, taken five-plus years.”

WHAT THE OPPONENTS SAY

“From the get-go of it, we caught wind just through the rumor mill that this proposed monument was being talked about and there was going to be some kind of press (conference) deal,” said Russell Johnson, a fourth-generation rancher in the area. “None of the ranchers that would be impacted by this monument were invited to it. We reached out to our state senator and state representative. None of them knew about it.”

Johnson serves on the state board for the New Mexico Farm and Livestock Bureau and is president of the Luna County Farm Bureau. Luna County is where the proposed national monument will be located. “None of them knew about it.”

Since then, there have been a few meetings to discuss the proposed monument. “There were several county commission meetings that discussed this and several City Hall meetings that discussed it. The city and the county, the City of Deming and Luna County, all passed resolutions opposing this. And then, the only other municipality within Luna County is the Village of Columbus. They also passed a resolution to oppose this.”

Beyond that, he said several counties scattered across the state have joined Luna County in opposing the Mimbres Peaks National Monument. They are Hildago County, Lee County, Otero County, Union County, Sierra County, and Chaves County.

“We started a grassroots movement through the Luna County Farm and Livestock Bureau called No Mimbres Monument. And we’ve got a Facebook page and a website. And the proponents, they’ve got a Facebook page and a website and that’s pretty much the only way that they’ve engaged the public on the matter, is just through social media.”

The concern by ranchers is the proponents have not engaged the community and the stakeholders who will be impacted, he said. For some ranches, the entire operation is within the proposed boundary. “And then, in our case, about half of our ranch is within the monument.”

Johnson said that proponents point to the Organ Mountains-Desert Peak National Monument as an example of how grazing hasn’t been impacted. “My argument there is, even though it’s been designated for over 10 years… they still haven’t developed a resource management plan for that monument.”

The resource management plan dictates how resources will be managed within the monument. “That’s where you’re going to start seeing the effects on landowners, and particularly stakeholders like ranchers. Because (that’s where) you really get into the guts of the rules and regulations of a monument,” he said.

That’s another point of concern. “We went to one of the meetings (about developing the resource management plan for the Organ Mountains-Desert Peak National Monument) and they told us usually these resource management plans take years to develop, which we’re already in year 10, but it seems like up until recently, they finally got serious about developing a resource management plan, but they’re trying to fast-track it and get something in place by the end of the year. And even the BLM was telling us that’s kind of not the norm.”

Then, of course, there’s the concern about being able to continue grazing cattle on federal land within the proposed monument. Johnson points to the Sonoran Desert National Monument in Arizona where he said that the grazing leases on the southern portion of the monument didn’t renew. “And then, to date on the northern portion where there’s still grazing, (environmental groups) have brought two or three lawsuits against the BLM basically to try to get the BLM to eliminate grazing on the remainder of the monument. So that’s a concern to us. Will our leases be renewed? Will grazing be eliminated right off the bat?”

He gives a nod to statements by the proponents that grazing will remain the same. “But our issue is, you can eliminate grazing from the landscape without saying that you’re going to eliminate grazing. And by that, I mean if you start changing the way we can manage this land in the sense of maintaining improvements with equipment versus doing it by hand or not being able to install new improvements. If a well goes dry, are we going to be able to get equipment in there to drill a new well, things of that nature?”

In Johnson’s mind, establishing the Mimbres Peaks National Monument doesn’t make sense. “The BLM’s already managing it anyway. And I look at it as we’ve got a pretty good working relationship with the federal government through BLM and we’re doing a pretty good job of managing these lands as it is. And there’s really no advantage to designating it a national monument.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Protect Mimbres Peaks: www.protectmimbrespeaks.org

No Mimbres Monument: www.nomimbresmonument.org

Organ Mountains-Desert Peak resource management plan: https://eplanning.blm.gov/public_projects/92170/200212669/20107574/251007574/OrganMountains-DesertPeaks%20Natl%20Monument_DEIS%20RMP_20240404_508.pdf

Economic Analysis: https://protectmimbrespeaks.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/MPNM-Economic-Impact-Report-Nov-29-2023-FINAL-V2.pdf